Sheikh Jarrah is a Palestinian neighborhood in Occupied East Jerusalem. If you had never heard of it before, it is more than likely that you now have. The neighborhood is at the heart of the ongoing ethnic cleansing campaign by the Israeli state. It has personally been very difficult for me to put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) and elaborate on the atrocities occurring in front of our eyes in historic Palestine, the roots of which have a long colonial history dating back to the late 19th century. Rather than a detailed timeline and political retelling of these events, I shall provide a personal account of my mother’s family, in their voices, mainly my uncle, of growing up in Sheikh Jarrah, Jerusalem.

Sheikh Jarrah is a predominantly Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem, and is named after Sheikh Jarrah, a physician of Salah-e-din, who’s 13th-century tomb can be found nearby. When it was founded as the modern neighborhood of today in 1865, it was a center of some of Jerusalem’s Muslim elite including the Husseini and Nashashibi families. After the 1948 Zionist invasion, it became the border between Israeli-controlled West Jerusalem and Jordanian-held East Jerusalem until its complete occupation by the Israelis in 1967. Today, it is home to many Palestinians who were displaced from their homes in 1948, and is the current center of Israel’s continued attempt to wash the city clean of its Palestinian presence.

Over the last five decades, illegal Israeli settlements have been built in and close to Sheikh Jarrah as a central part of its ethnic cleansing strategy. The illegal expulsions of Palestinian families have been funded by rightwing donors in the United States. The current round of forced expulsions began in early May when the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that six families had to vacate their homes to make way for more Jewish settlements. An additional seven families have also been ordered to vacate later this summer. In total, 58 people, including 17 children, will be forcibly removed. Throughout April and May, Israeli authorities joined forces with Jewish settlers to harass and intimidate the Palestinian families living in Sheikh Jarrah. Videos of violence against the peaceful protestors at the hands of Israeli police-backed gangs of Jewish settlers have since gone viral. Attacks on worshippers at Al-Aqsa mosque soon followed, with warnings from Hamas to the Israeli government to cease its attack on Islam’s 3rd most holiest site. Without fail, the Israeli authorities increased their assault on worshippers and protestors goading Hamas into firing its crude rockets at Israel in defence of Al-Aqsa. What followed was an intentional massacre unleashed onto Gaza by the Israeli state, which left over 200 Palestinians dead, including 66 children.

I am not ashamed to say I wept. I wept for every child, mother and martyr. I wept for my maternal grandfather and paternal grandmother, both of whom passed away two years ago, defiant and resilient to their last breaths, much like their beloved Palestine. It seemed that with every death, it felt like I was losing them all over again. I spoke with my mother, my uncle, and my maternal grandmother over the phone desperately trying to revive and relive what was described to me as the best years of their lives in Sheikh Jarrah, in our beautiful Jerusalem.

My maternal grandfather, Tayseer Kanaan, held several judicial postings throughout the West Bank, the final of them in Jerusalem until the Israeli invasion in June 1967. Refusing to work under the Israeli courts once Jerusalem was occupied, he went on strike and led efforts to resist the Israeli occupiers of his beloved Jerusalem. It was into this environment that my mother and her siblings were all born in Jerusalem between the years 1960 and 1964. Speaking with each of them, I couldn’t help but notice the joyous, bittersweet tone their voices took when telling me of their childhood and young adult years. I was surprised. Perhaps I was expecting more sadness, anger, perhaps even anguish? My uncle said to me: “They will never take away my memories, the beauty of my childhood, and the fortune of growing up in the heart of the most beautiful place on Earth.”

Siham’s maternal uncle on the left

We grew up riding bicycles up and down the hilly streets of Sheikh Jarrah. The neighborhood was like a lush forest filled with trees. I remember the Cupresses and pine that fell everywhere and covered its streets. I remember picking up the pine and fallen leaves and throwing it at my sisters and friends in the neighbourhood. Our friends were all from the neighborhood. I never saw my school friends except in school. We stayed outside chasing each other on our bikes, climbing trees, and running after one another until it turned dark and all the mothers would step out onto the pavements in front of their houses and yell for us to come inside.

The Al Kharoof Market was a close five minute walk from our house, where we would run to buy all our chocolates and snacks. We, of course, pretended to “wait until after our dinner” to feast on them. One of our neighbors had a tree house where we used to sneak off to play and eat the contraband, far from prying maternal eyes. We would of course come down from the tree houses as soon as we heard the ice cream vendor pushing his cart up the steep hill and calling out at the top of his lungs “BOOZA, BOOZA,” (Arabic for ice cream).

Our neighborhood was like a forest. Everywhere you looked was greenery. The trees in Sheikh Jarrah are more than 100 years old. You could always hear the strangest noises in Sheikh Jarrah in the middle of the city. At night, when it was quiet, we would hide under the covers imagining all those creatures making all that noise making their way into our homes and into our rooms. I often wondered at how old the birds were that flew from tree to tree, always singing from their perches about the secrets of the neighborhood. You could probably still find all the engravings we made as children of our initials or of the initials of our childhood loves sealed with hearts.

Aldrich and Symonds Map of Jerusalem – 1841

Sheikh Jarrah was home to all the foreign consulates and it was a mix of local Palestinians and foreigners from all over the world. The neighborhood was, for the most part, owned by traditional Jerusalemite families divided between two of the oldest: the Nashashibis and Al Husseinis. The Orient house was an eight minute walk from our house where the Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini lived. Our neighbor was the famous Palestinian scholar, Isaaf Nashashibi, his beautiful house now a museum and school for children. Sheikh Jarrah was the central heartbeat of Jerusalem.

My grandfather’s friend and nephew of Isaaf, Nassereddin Nashashibi, lived across the street. He had a large garden where we used to go and play. His house is better described as an ancient castle, so spacious and old it was. But that was Sheikh Jarrah, all of the houses were like that. Next to our house was the Lebanese consulate, also rented from a Husseini. Rohi Basha Abdulhadi’s house, my great uncle, was also close by and was rented to the Belgian Consulate. There is a majesty to Jerusalem that cannot be put or encapsulated into words.

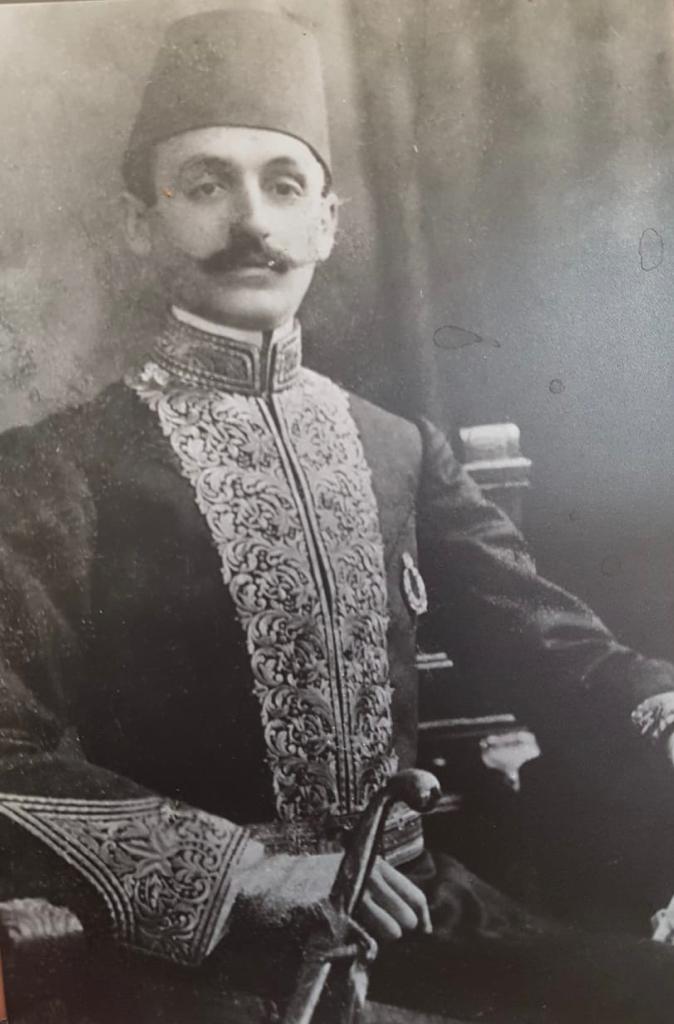

Rohi Basha Abdulhaidi – Siham’s great uncle

Ali Baik Al Husseini, our neighbor, was a graduate of the Sorbonne. He was always in a bowtie and tarboosh walking up and down the hills of the neighborhood with his cane. He was always on his way somewhere with his trademark attire.

Everyday, at precisely 5 pm, I would watch another neighbor, Jawad al Husseini, and his wife set out their finest China for afternoon tea on their balcony. Whether they had guests or they were alone, Jawad and his wife were always dressed up. Him in a suit and tarboosh, and her in her fashionable dresses.

I attended the French school in Jerusalem. I would walk over to Jawad’s house so that his wife could teach me French. We called her Um Ghaleb, or “mother of Ghaleb.” Jawad’s father, Abu Hisham, was also a graduate of the Sorbonne in the early 1920s. He also used to help me with my French, despite being well into his 90s.

Dr. Khalil Budeiri, the husband of my grandmother’s cousin, lived next to us on the other side. Despite being a medical doctor, or perhaps because of it, he had a severe phobia of germs. He never let anyone into his house for fear of the germs they would bring in, and on the rare occasion that he did, he would send his wife and the house staff into fits of anxiety frantically cleaning up after any guest came and went. Something his wife would detail in great exasperation to my mother over morning coffee. His germophobia was so severe, he never opened his mouth for fear of bacteria getting into his body via his mouth. I am not exaggerating when I tell you that we never heard him speak. We only heard grunts and hums of agreement or disagreement from him, his mouth tightly sealed. I used to walk behind him up the hill to our home after school everyday. He carried a cane and walked up the hill in a zig zag pattern. This was my daily scene after school, following the zig zag trail behind Dr. Khalil Budeiri humming or grunting at anyone who greeted him along the way.

My uncle continued recounting the tales of his childhood, of his beautiful home and city. All the stories and houses he described to me owned by old Jerusalem families with deeds dating back over 300 years. We continued reminiscing and laughing over his memories. I found myself feeling lighter, the heaviness lifting from my heart as I remembered why we continue to fight 73 years later. He left me with this:

Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood is where I was born. I lived the best days of my childhood in this neighborhood, even some years past my graduation from high school. I still remember the scent in the air. I envy the birds and the Yasmine trees of Sheikh Jarrah. The Israeli occupation thinks it can erase us by denying me my right to visit my home. I pledge I will return no matter how long it takes, and hopefully with my children too.

Siham Nuseibeh

As told to me by my dearest uncle ‘KK’ Khaled Kanaan.

I dedicate this to my grandparents and to our martyrs.

We may grow old, but we will never forget.

Rest in Power.

(Images courtesy of Siham Nuseibeh and Wikimedia Commons)