Growing up in the Levant I was exposed to the beautiful fabric called ‘sayee’. A bright multicolored, striped fabric with a singular sheen, woven from a blend of cotton and silk, both matt but shiny, difficult to describe.

It could be found in every self-respecting Levantine household. My mother had ‘dishdashas’ made from it. It was used for about everything, ranging from furniture upholstery, curtains, cushion covers, quilt covers, book covers to tissue boxes. If you could cover it, you did it with ‘sayee’!

I was also lucky to visit Syria often, almost on an annual basis. My parents and godmother were interested by handicrafts. I was exposed to many of Syria’s talented artisans, including to the incredible ‘sayee’ weavers.

This fabric is the high point of my visual memory, so, you can imagine my surprise when I came across this beautiful striped fabric in India.

I had been offered a stunning bolster for my birthday that was made from the exact same fabric.

“Did you get this from Syria?!” I asked my friend, who on seeing the expression on my face knew that she had picked the right gift.

“No, no, this is local, I think it’s woven in Gujarat.”

That’s when I started my investigations! I searched high and low, asked every weaver, textile scholar, shopkeeper I knew if they recognized the fabric. They all had the same answer and story, it was ‘mashru’.

“Mashru was created by the Muslims. That ‘mashru’ derived from the Arabic word, ‘masmooh’, meaning authorized. As in some parts of the Muslim world it was frowned upon for men to wear pure silk. The Muslims introduced the technique of weaving cotton in the weft and silk in the warp. This allowed the silk not to be in direct contact with their skin, but allowed their clothes to maintain a shine, and as the Muslim men in India needed a fabric that was striking and ‘masmooh’ (authorized) that is how it started.”

I was intrigued and baffled. The story sounded like a fable. First, being from the Middle East I had never heard that it was forbidden for men to wear silk, and second did ‘sayee’ really come all the way from India to the Middle East? I mean of course, with the trade of the Silk Roads, it was possible.

Needing to find answers I invited a dear friend, Simon Marks, over. I knew he would be able to help, he knows India’s world of handicraft like very few others I know. He is fluent in Hindi and has traveled across India, living for a while in Bhuj. I was sure he would know.

“Of course Darling” he immediately replied, “book a ticket down to Ahmedebad, take a bus or a car down to Patan, and I’m sure you’ll find what you are looking for.”

I did that. The following few days I organized to fly down to Ahmedebad to see what I could find. Once in Ahmedabad, I was driven around by ‘Jonni’, Simon’s friend and excellent contact. I was able to visit every fabric vendor dealing in ‘mashru’ whom I could find. They all told me the same story about the origins of ‘mashru’ – that it was woven for Muslim men, that it was out of fashion, hard to find, and that whatever was available today was synthetic.

Different vendors taught us how to check if the ‘mashru’ was handloom or a machine made imitation. It was interesting, unfortunately, they were right. Handloom ‘mashru’ was difficult to come by.

Jonni told us we should make our way to Patan, that he knew several people who were still weaving it there. None of the shopkeepers whom we spoke to were of that opinion, they all claimed that the weavers of Patan just produced Patan ‘patola’ (another extremely intricate form of tie dying and weaving). Jonni took a wager and said that if he was wrong I could ask for the sum of my choice.

The day we traveled was Vishwakarma Jayanti, the day craftsmen clean and prepare their tools for a blessing ritual, and cannot use them on that day. Which meant that we would not be able to see any weaving taking place. Not the best day to visit, but we had no choice!

We arrived at Patan, a small town which was the capital of Gujarat in Medieval times. The architecture of the place is incredible. Small village type brick and mortar , and what appeared to be almost European style town-houses. We asked a few people from the town if they knew any weavers, they all pointed us to a lane. A tiny lane that led to a building where we were told that the main family dealing in ‘mashru’ lived. This family gathered all the weavers’ finished products and exported them to different cities across India.

We walked down this muddy lane and came face to face with a bull who didn’t seem to mind so much that we were there. We noticed that right up against the windows of the houses, there were small cushions of the type weavers who work on narrow looms sit on, but no sound of shuttles going up and down. It was an important day, the looms were being prepared for annual blessing.

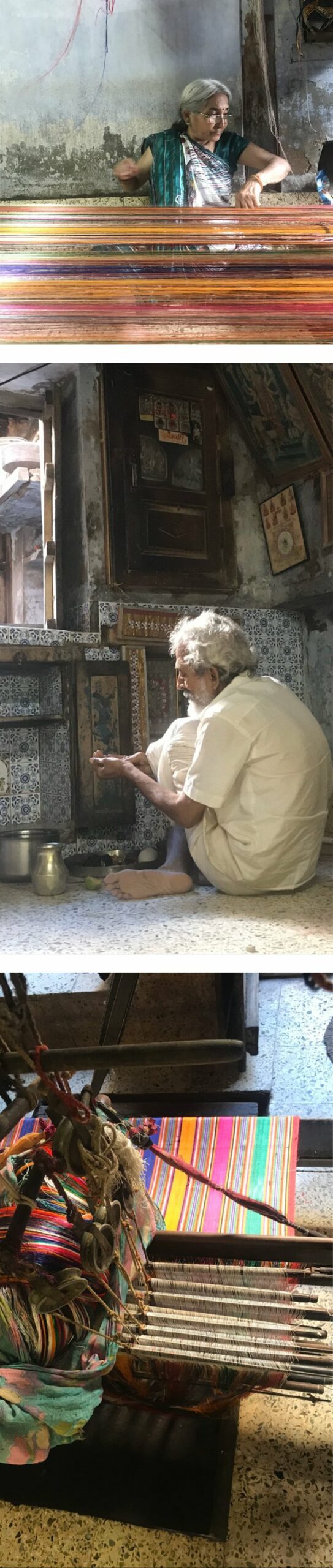

We saw an old man who looked over 80 collecting water from the tap outside his house and preparing to wash his tools. We asked if we could come in and speak with him. He didn’t seem very interested in us, barely looked in our direction and gestured towards the door. We followed him through a tiny courtyard into his magical house. He left us standing in the middle of the house, sat on the floor and vigorously continued to polish his tools.

The tiny house had low ceilings. On top of the narrow loom on the right of the entrance, the ceiling was lower, and a wooden tub seemed to project from the ceiling above on either side. They sensed that we were puzzled. Without looking up the man said “those are two other looms, upstairs, my brother’s and his wife’s.”

His sister in law suddenly appeared behind us. Old, energetic, not at all surprised by our awkward presence in their home. Her husband appeared at the top of the stairs that led to the floor above. He sat on the stairs and watched us, silent and smiling, as though he were watching a spectacle unfold.

When we informed her about our quest to find ‘mashru’, she told us that we had come to the right place. ‘Mashru’ was the only thing they knew how to weave. They didn’t think that many ‘mashru’ weavers still existed – only a handful in Patan. That this was all they did, day and night, that no one else would, and that their children wouldn’t carry on with the craft. It was sadly true, as it was becoming too expensive to buy silk thread today. Once a year they only wove a few ‘thans’ of ‘mashru’ using real silk for the Indian clientele who still appreciated it. We told her how happy we were to find them, and that we hoped their beautiful trade would never come to an end. She smiled and jumped to her feet, and declared with excitement: “if I don’t weave too much, it would be a demonstration that wouldn’t go against Vishwakarma Jayanti”. She began a beautiful demonstration, while explaining the whole process and how to go about it. In Gujarati of course, almost as though she believed that she can hand down the skill to us.

I showed the wonderful weaver pictures of ‘sayee’ and explained that it was something I was familiar with but not from her area, but from Syria. To which she replied “of course, you know that fabrics travel far more than humans do, and from longer distances.” I was mesmerized. I didn’t want her to stop talking. I asked her if she knew of the story of ‘mashru’ being created specifically for Muslim men, and that the name ‘mashru’ came from the Arabic word ‘masmooh’ or authorized. She looked at me in complete confusion. She explained that Gujarat was an ancient port, and at one time was India’s most important port. That all the tribal people wore ‘mashru’, the women used it to make blouses, the men to make formal wear. No matter what religion, it was just a matter of being economically able to purchase it, and that even a woman with no formal education like herself knew that.

Finally she told us before she asked us to leave so she could get on with her ‘pooja’ and that “in Gujurati ‘mush’ means silk and ‘roo’ means cotton.”

Find mashru in our noon collection

Nur

(Images courtesy of Nur Kaoukji)